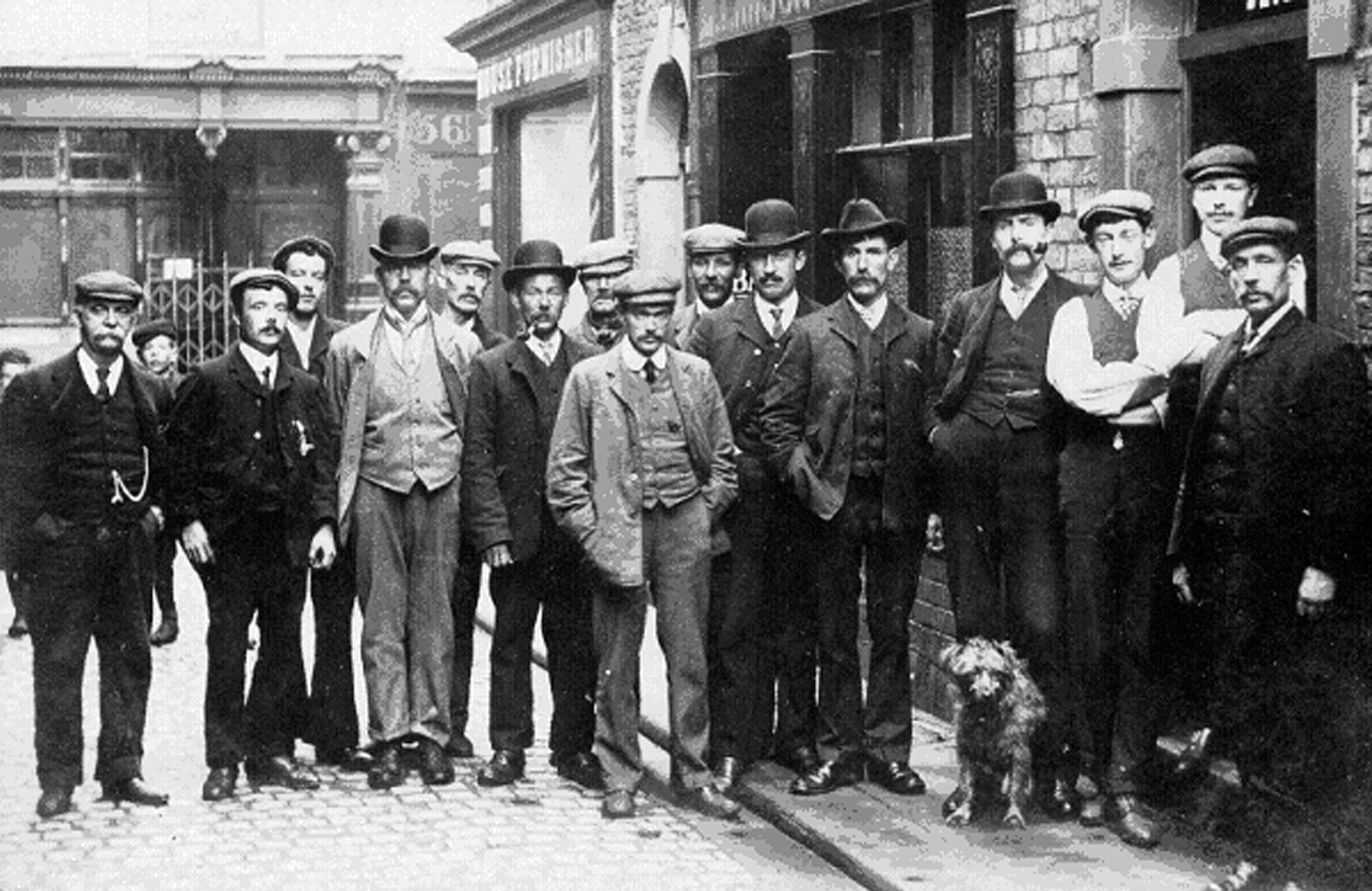

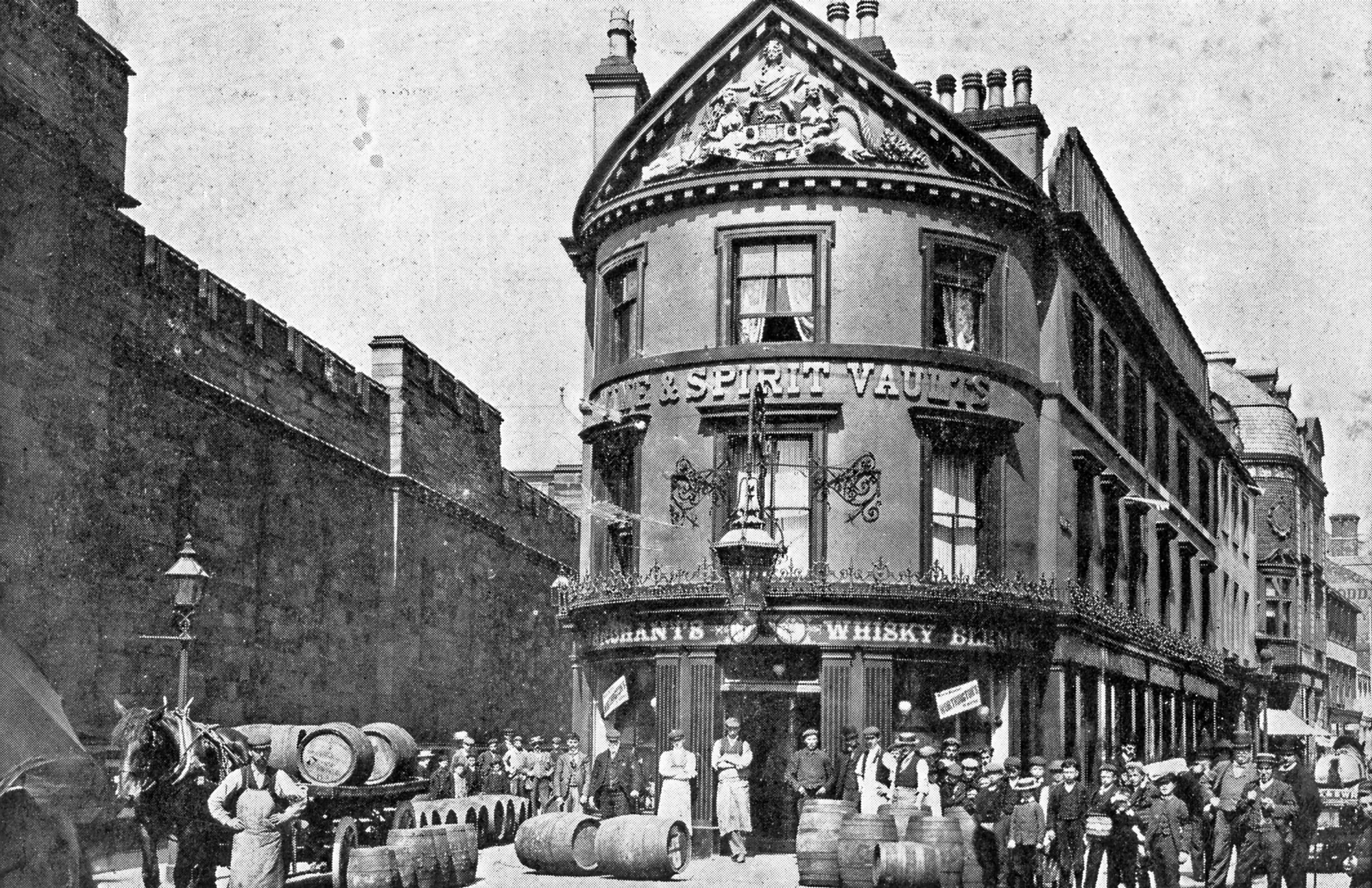

Drink premises in Carlisle typified the Victorian gin palace. Exteriors boasted multiple front and back entrances, huge signboards, prominent liquor advertisement, bottle displays, and vast gaudy mirrored windows. Inside, partitions and snugs divided rooms into small, drab, ill-lit, unhygienic, smoky, stuffy areas with tawdry decor. The public bar had no seats, bar counters facilitated “perpendicular drinkers”. Smoke room customers got seats, but paid for them with dearer pints. Drinkers received nothing more here or in the public bar: no food, games, entertainment, or even comfort. One critic not unjustly dismissed such pubs as “poky little drinking dens”.

Into these cramped, seedy quarters, respectable women dared not venture. “Men in certain parts of the city”, Albert Mitchell acknowledged as General Manager of Carlisle, “would not have the women drinking with them.” Decent women were deterred by periodic fights between rival groups in Carlisle’s most depressed areas and by the persisting social stigma of public drinking in less violent localities. Prostitutes mingling with prospective customers in public bars would have been equally off-putting. Only the most downtrodden women, therefore, sought leisure in the pub. Ostracized by male solidarity in main drinking rooms, they resorted to drinking in peripheral unclaimed space – doorsteps, passageways, and “jug and bottle” (off-licence) departments.

BUT, this is not the true story for all the pubs.

Take the Wellington for example which stood opposite the Gaol Tap (and is now home to “Outrageous”). The Wellington was built in the 1850’s and included a Baronial Hall which was fitted out with oak panelling and doors, suits of armour, helmets shields and pole axes. A Souvenir brochure produced by John Minns in 1918 entitled “Ye Olde Baronial Hall” says “it gave such a feeling of peace and contentment as if you had stepped back into the days of old when knights were bold”. There is little doubt that it was years ahead of its time, yet it was gutted by the Central Control Board shortly after they took over. An example of civic vandalism!

The Central Control Board introduced imaginative policies aimed at raising the image of the pub. The Board also saw that it had a role in initially excluding women from licensed premises. Architectural changes instituted under State Management revolutionised assumptions about exteriors, layout, and functions of the pub, destroying sharp distinctions between hotels, restaurants, and private clubs for the privileged on one hand and drink premises for the poor on the other.

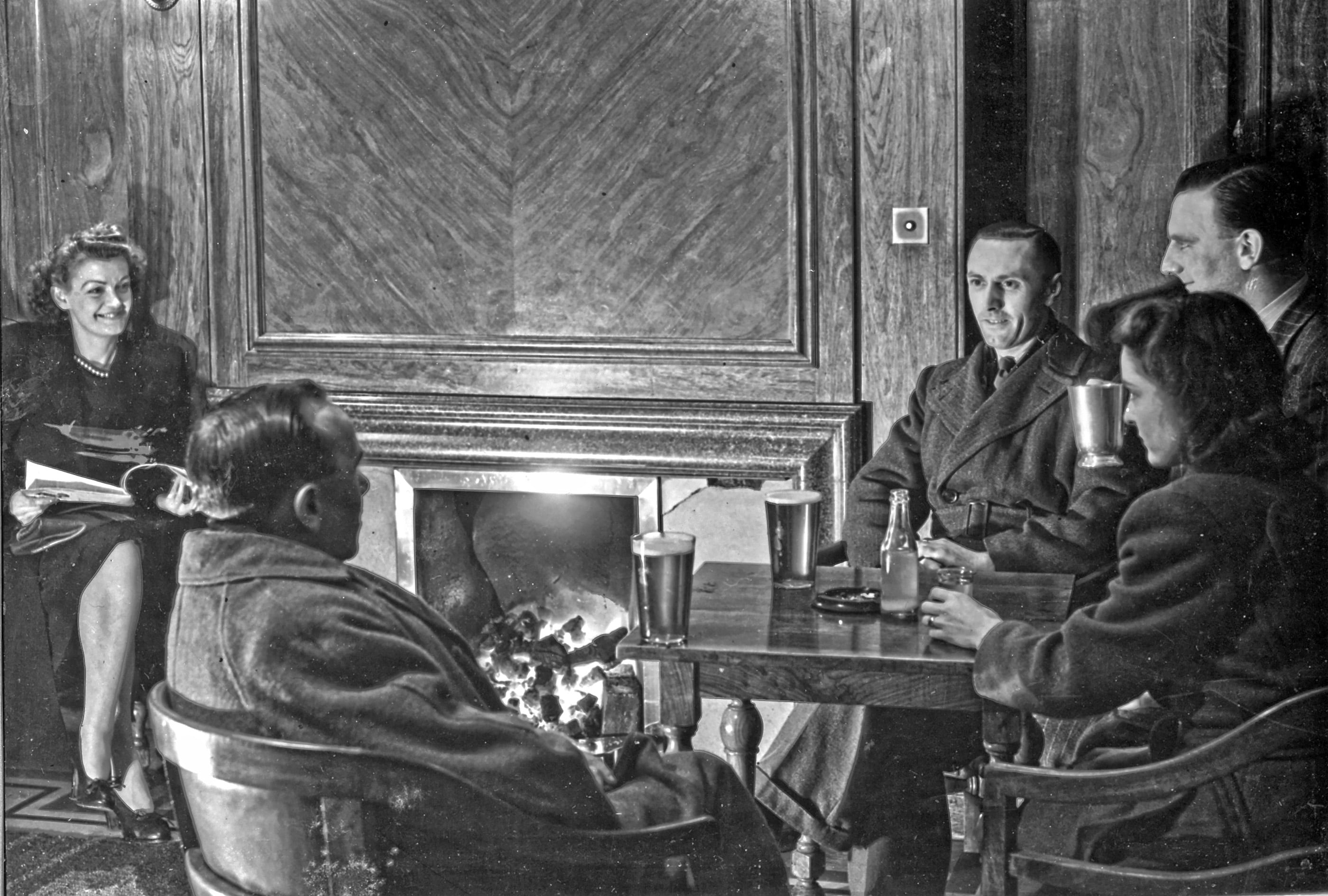

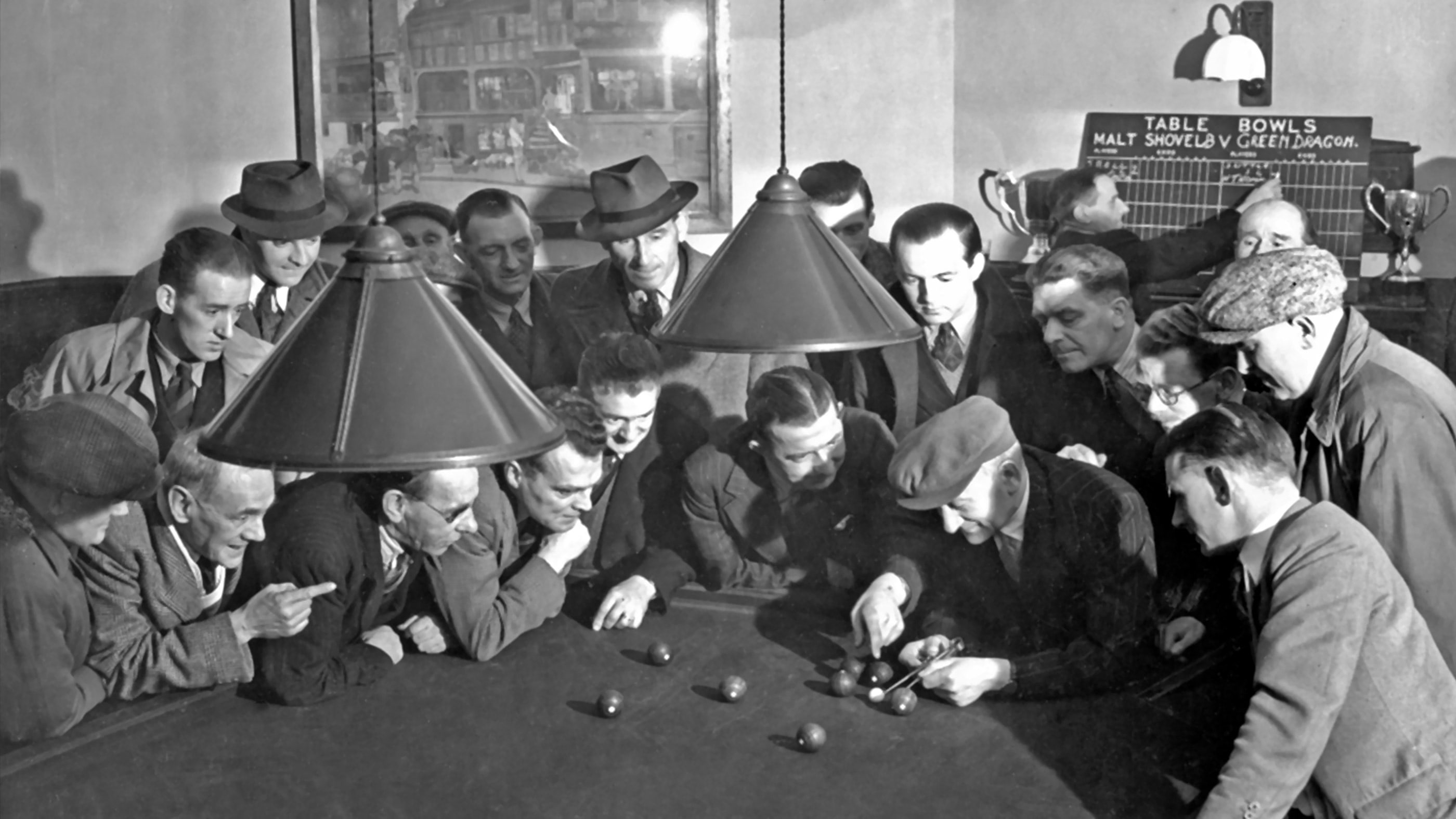

No longer would class and gender segregate leisure activities in public spaces. Public Houses lost all trappings of classic Victorian gin palaces. Outside, back entrances were closed, a discreet shrunken house name appeared above the door or on the wall, and subdued green curtains graced unadorned windows. “There is no more indication that the house is a public house than is absolutely necessary,” remarked an amazed Birmingham Daily Post reporter visiting Carlisle. Interiors, too, bore the reformers’ stamp. Partitions and secluded snugs disappeared, transforming stifling, gloomy, dark rooms into cavernous quarters, as striking for their vastness as for their light, openness, and ventilation. Redolent of posh hotels, the seats, tables, chairs, and truncated bar counters promoted sociability as consciously as the waiters who replaced bar service in saloon bars. Board reformers also laboured to introduce aesthetic decor, described by one enthusiast as “utility with beauty”. White cloths and flowers bedecked tables, and artistic prints and lithographs, illuminated with shaded lamps, lined walls and projected a homelike quality. Immense, undivided café or restaurant rooms, creating a hybrid between pubs and restaurants, most symbolically rejected traditional pub architecture.

The Carlisle experiment was an important moment in the progressive reform of the pub, with the Scheme being an “experimental laboratory and microcosm of the entire industry” which provided “a tested blueprint for post-war reconstruction” (David Gutzke in his book, Pubs and Progressives).

Lord D’Abernon, Chairman of the Board, called it, the “model farm” a place where ideas and plans, which had previously been nothing more than idealistic musings concocted and discussed in Board meetings were implemented. The Scheme exemplified the Board’s most radical ideology and shows what the Board had in mind if the Scheme had been rolled out nationwide.

But the Scheme suffered from a problem of presentation. Regardless of how the experiment was framed, contemporaries saw the Scheme as a temperance project. Any attempt at controlling the consumption of drink was by its very nature temperate action but the mutual antagonism that existed between each of the interested parties in the drink debate meant that the experiment could not openly be described as a “temperance experiment” as it would have been politically insensitive to do so. Carlisle was therefore justified due to “national efficiency” concerns, social reform not temperance reform, even if the outcomes were similar, was the supposed justification for the project. This flimsy distinction was unimportant to opponents of the Scheme, which included prohibitionists and trade activists, and caused many problems for the Board. The Board had not been established as a temperance body but as Lord D’Abernon recalled, “[the actions of the Board] constituted the first attempt to deal with the drink traffic solely on lines of national efficiency, any other aspect of the problem having been barred by the terms of reference.” The fact that “temperance” ideas were being tested was justification enough of the Scheme for the Board but angered others. These varied opinion and interests make the Carlisle experiment symptomatic of the debates that occurred over the wider struggle to control alcohol consumption during the First World War and continue to the present day.

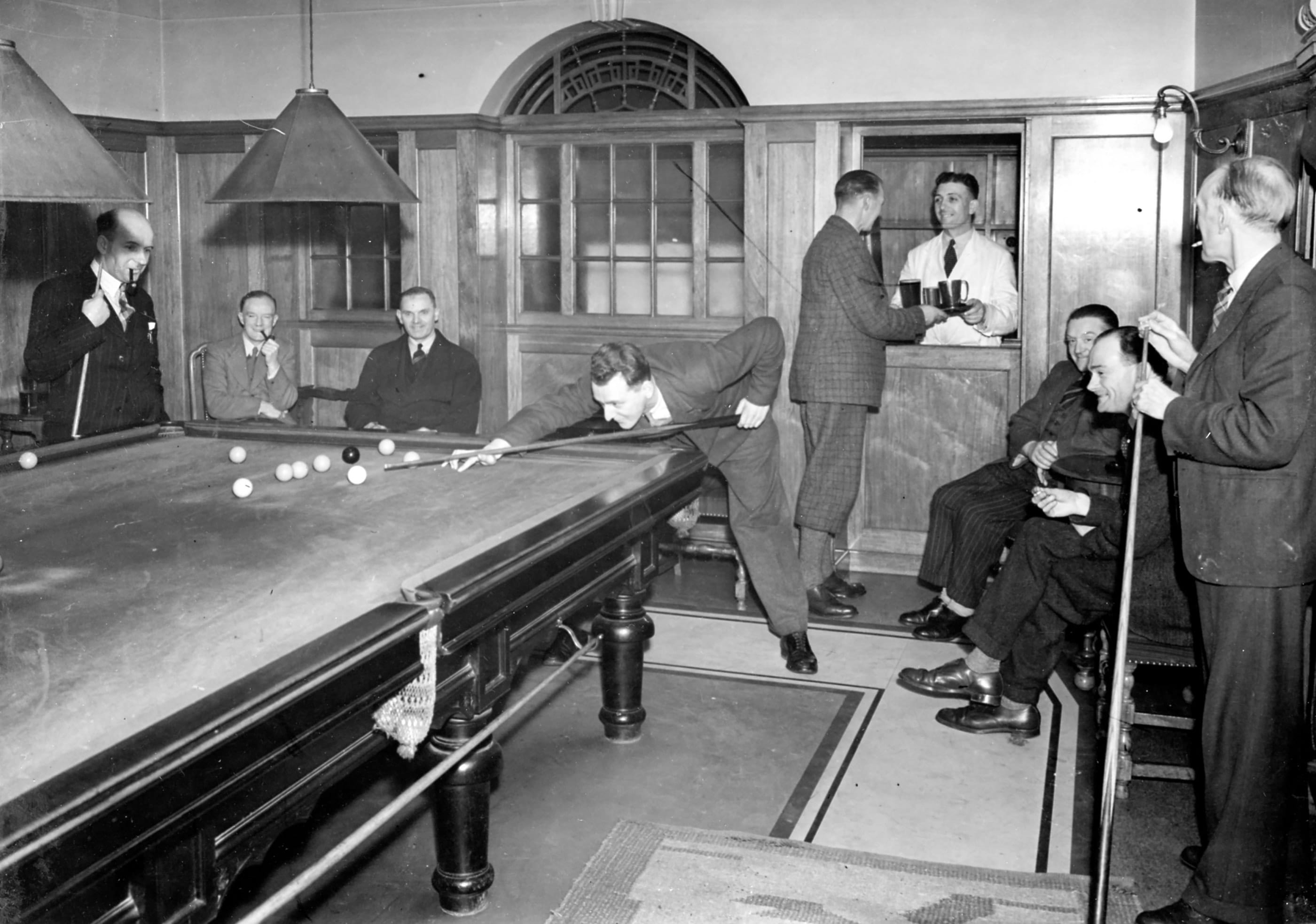

In many ways the most significant practical impact of the Scheme came about with the changes in the design inside and outside of pubs (the Redfern effect) the introduction of games and past times such as bowling greens and the introduction of food into pubs. But that’s a story for another day.

The Carlisle experiment of “Disinterested Management” was, however, only part of the approach. There was a deliberate policy of transforming the public house itself. The general state of public houses throughout the country was far from satisfactory. Most were cramped, overcrowded and unhygienic.

Carlisle had provided the opportunity to experiment in this field. Nearly half the existing public houses were closed, while the rest were radically ‘improved’. There were some initial complaint about the removal of ‘snug’ bars, but the general consensus was that, after a decade, the Carlisle drinkers were satisfied with their regime.

During wartime, the emphasis in the scheme had been upon the elimination of drunkenness and the promotion of temperance; however, in peacetime a subtle shift took place. By 1925, for example, a new policy was introduced for providing comfortable women’s bars, in place of the previous practice of encouraging women to drink in side passages or in spartan standing bars. Carlisle not as a mere commercial enterprise but as ‘a sort of missionary centre’, but the gospel which was preached after the war was not one of temperance but of ‘the improved public house’.

This was picked up nationally by many private brewers Whitbread being a prime example and gradually food, comfortable seating, leisure facilities were introduced modern spaciously designed pubs were built on the Harry Redfern model.

But it got a new debate going was it right to establish licensed premises of the character of a restaurant in which games are played? Do not such houses attract a class of person who would not go to a public-house? Youths and young women for example? If people want to play games why should they go where alcohol is sold?’

Such questions went to the heart of the debate about the ‘improved’ public house. But the future was to lie in commercial exploitation of the pub as a leisure facility with as much profit coming from non-alcoholic ancillaries such as soft drinks, food and games as from alcohol. The pattern was already set, even though it was only as late as the 1960s that it became universal all over the country.

Carlisle had led the way but the debate continues!

Evidence that it was only intended to last for the duration of the war

“All we have to do at the moment is to give the Government such powers as are necessary for the specified purposes for which they ask for them. They ask for them in order to regulate the sale and supply of intoxicating liquor in any area where they think it should be controlled by the State, on the ground that War material is being made, or loaded, or unloaded, or dealt with in transit. That is the primary and the great ground of necessity put forward. It is really in connection with the supply of munitions of war that this Bill is introduced. When the War comes to an end that special necessity will come, to an end; the real reason for the Bill will be at an end, and the sooner we can stop our liabilities in the matter the better it will be.”

Extract from Hansard 5th November 1915

There is no definitive answer to this question.

Probably the two main reasons are:

- It made a profit every year for the government

- The economic and political problems facing Britain in the twenties and thirties that ultimately led to the second world war and the rebuilding problems in the fifties and sixties were far more politically urgent than dealing with State Management of pubs in Carlisle.

Again no definitive answer but two possible reasons:

- Constant lobbying by the brewers who were major funders of the Conservative Party

- A Conservative government totally opposed to any forms of nationalisation and the state managed pubs were an easy target.

A series of government leaks to the media that led to an unscheduled announcement by the Conservative Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling MP to the House of Commons who explained that, “…there is no longer sufficient, social or economic justification for the continuance of State Management of the liquor trade. Return on capital employed is low in view of the restrictions under, which the Scheme operates: and there would be a need for further substantial investment of public funds if the present Scheme were to continue. I accordingly propose to wind up the activities of the Carlisle and District, State Management Scheme”. Hansard, Issue 844, 19th January (1971, pp. 272-273). Thus, the major argument for privatisation was based on the premise of financial inefficiency and reducing tax funded expenditure which had no economic justification. The other coded reference to a lack of social justification was to reverse the process of collectivism which was an anathema to the new political right. In the subsequent debates the government’s financial argument for justifying privatisation remained largely unchallenged, and became obscured in the ensuing doctrinaire party political exchanges.

June 1976 marked the end of a dry spell

When State Management was introduced in 1916 one man refused to sell. The landlord of the White Quey, Stoneraise, Durdar was so determined that his pub would not fall into Government he closed it down completely and said in his will that the building was never to be used again as a pub. And that remained the position until Eddie Gash and his wife bought the building in 1975. After a long legal battle the original owner’s grandson was found and he agreed to rescind the order. Mr and Mrs. Gash spent 18 months renovating the building and in June 1976 it reopened as a pub.